Why Do You Want to Be a Doctor?

It’s a question all medical students are asked when they apply for medical school, many whilst still a teenager. I recently spoke at James Cook University in Townsville, and one the students there asked me the same question again 12 years later. I found that my answer had significantly changed.

Growing up

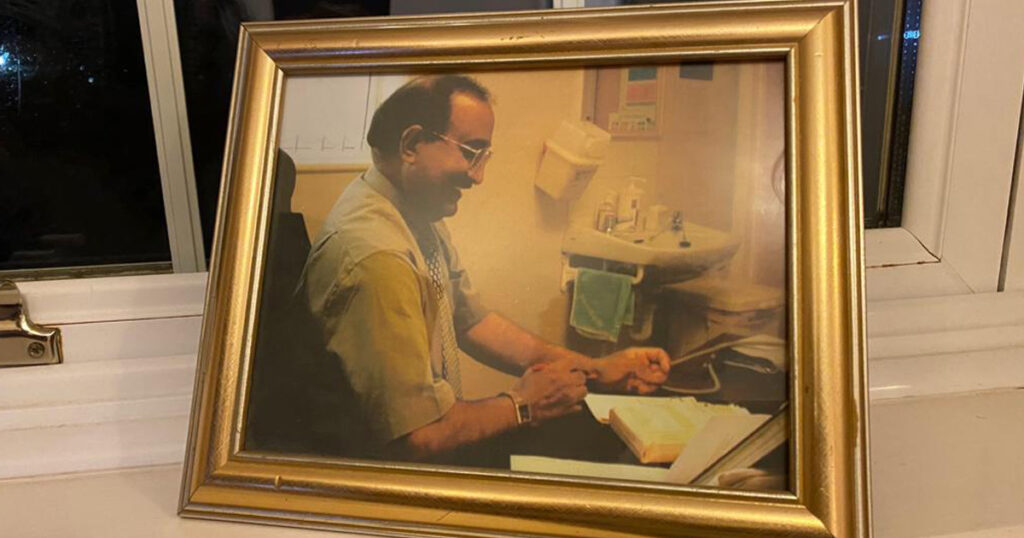

Having a father as a primary care physician meant that I had a day-to-day example of a doctor in action. Whenever I asked him, “Dad, what makes you want to be a doctor?” he would say “I enjoy helping people”, simple as that. I remember him popping up in an edition of “Reader’s Digest”, a magazine in the UK. A patient had written to readers digest to tell them about how my dad had come around for a doctor’s visit, and he had ended up helping her to trim the hedges in the garden after the consultation. He saw that his patient was too sick to maintain the garden, and that the garden was one of the few pleasures that his house bound patient had in life.

His motivation to be a doctor delved a lot deeper than that as well. His family left their home and all their possessions when my dad was aged 3 to move to the newly formed Pakistan in 1947. In exchange for living in an Islamic nation, they lived in poverty. He grew up without electricity, without money for public transport, without a desk to work, without many of the resources that you would associate with a good start in life. And so he worked hard. Really hard.Studying under street lights in the evenings so he could see his textbooks. Walking 3 hours a day to get to lectures. He worked hard because he wanted to become a doctor, so that he would have the money to support his brothers and sisters, and to support a wife and children of his own in the future.

if I am being honest with myself, was motivated by the idea of being thought of as a doctor, a profession associated with being intelligent, caring, and dedicated. I liked the idea of developing those qualities in myself.

Applying to medical school I grew up in a South Asian, Muslim family. When I applied to get into medical school, I was told lots of things by different people. Some people said to me “Zeshan, you’ll be able to get to heaven easier, because working as a doctor forces you to do good deeds every day”. Other things said to me include “Zeshan, if you work hard and become a doctor, I’ll find you the most beautiful wife, you’ll have earnt it”. My motivation superficially was that I wanted to help others, and I thought medicine could have the biggest impact. But also, if I am being honest with myself, was motivated by the idea of being thought of as a doctor, a profession associated with being intelligent, caring, and dedicated. I liked the idea of developing those qualities in myself.

The process of applying for medicine though was marred by universities judging whether your motives for doing medicine were correct on incorrect. As such, I found that I was pushed into thinking what my school told me to think. So on my university application form I wrote the standard clichéd stuff: That I wanted to be a doctor because no other profession combined the opportunity for patient contact, and the opportunity to pursue a scientific understanding of the human body. It felt like, I was told what the correct answer was, and I was discouraged from expressing myself honestly. 12 years later I have now been working for six years as a doctor. I have a much fuller understanding of the reality of the job. If I was asked why I am a Doctor, my answer would differ significantly from what I said many years ago when I was interviewed for medical school.

The main reasons why I enjoy my job are:

i. My interactions with patients

The human face of medicine is the sick and vulnerable patient. They come to you asking for help, or in such extremis, that all you interact with is a broken body. The impact starts from the very basic. Being able to acknowledge the patient as an individual, and giving them the opportunity to express their concerns about life to an attentive ear. Just providing patients with an opportunity to speak and be heard is enormously empowering. Of course there is the ‘heroic’ life saving.

To take one of many examples, I remember attending a perimortem section: this is when a pregnant woman has had a cardiac arrest, depriving both her and the baby of any blood supply. The baby was carved out in about 20 seconds; no anaesthetic was used as the mother was already unconscious. My team and I resuscitated this baby- a baby that would have been stillborn in most parts of the world, while the babies’ mum received chest compressions and adrenaline. At 8 minutes of age, our efforts were rewarded when the baby started breathing; meanwhile the baby’s mother went onto her eighth round of adrenaline. Both the mother and the baby went to intensive care, but within just one week, both were home! And the mum’s biggest complaint was that her baby had a blocked nose! How could you not find being involved in such a case overwhelmingly satisfying?

As a doctor, I think it is an honour and a privilege to be given the opportunity to guide and support families through difficult emotions and uncertain times.

Obviously, not all patient interactions result in lives being saved. Often, despite all our best efforts, a disease becomes terminal. As a doctor, I think it is an honour and a privilege to be given the opportunity to guide and support families through difficult emotions and uncertain times. I remember once, I was talking to a patient, and mid-sentence, their face went purple, there jaw dropped and they fell back into their bed. At that moment, we later found out, the patient blew a hole in their heart. We couldn’t save him, but his family thanked me when I gave them the bad news. I didn’t understand how you could ever be thanked for this, but I have more insight into it now. As a doctor, these kinds of conversations can seem routine, ‘just a part of the job.’ But for patients, conversations about the end of a relatives’ life, are things which they will remember for the rest of their life. And if you as a doctor, are able to effectively communicate, i.e. if you help them understand what is occurring; if you demonstrate empathy and kindness; then as a doctor you can help the patient and the family avoid a huge amount of needless suffering.

The majority of my interactions with patients aren’t as dramatic as the above examples. But even very simple things can make a meaningful difference. Something small: I was working on the cancer ward, and there was a patient with breast cancer that had come in with a headache and vomiting. We were concerned about a possible brain tumour, but the headscan was normal. Subsequently, she needed to demonstrate she could tolerate eating before being discharged, but there had been issues with meals coming to patients that day. I did something simple: I found a toaster and some butter in the staff room and made her some food. She was able to go home an hour later, after we’d sat together and eaten.

ii. The broader societal influence of doctors

Even as a medical student, I remember seeing people’s eyes light up when I told them what I was training to do. Doctors are still arguably the most trusted professionals, and are associated with having an intellect and a moral fibre. This means that doctors can mobilise large groups of people to help achieve broader societal change. For example, I have been able to engage the public on issues that I feel are important, through unique access to media and specialists. I have been able to get involved in radio, television, and newspapers talking about issues such as stillbirth, the NHS, and mental health.

iii. Inspiration

Medicine, inspires me constantly. Of course there are brilliant pieces of work done by senior clinciians all the time, but I’m also inspired by my junior colleagues, and by medical students. The last book I coedited was “The Unofficial Guide to Medical Research Audit and Teaching”. It was led by a then medical student- Ceen-Ming Tang. She wrote and edited the book before she even graduated, and if that’s not enough, the book won a prestiguious prize at the British Medical Association Awards! As a paediatrician, the children I see are incredibly inspiring, and many are very resilient. For example, one child I recently saw was an orphan who had been kidnapped from their orphanage, and taken to Vietnam, where people tried to force her into prostitution.

He was in a position where his freedom was most restricted, but still did something really positive with his time.

She ran away, and was befriended by a lady who adopted her as a step-mum. But then her step-mum died in a plane crash. At her step mums funeral she met her step-mother’s friends, who said they would create a new opportunity for her. She was sent to the UK and entered a foster family here. Despite all the trauma she had experienced, she was determined to work incredibly hard. She has a hunger for making the most of life that is infectious. She is only a teenager, but she has already defied the odds, and achieved more than most her age. Her future, right now, is very bright indeed. Inspiration can come from such a wide variety of sources – some you wouldn’t even think of. I remember once on a forensic psychiatry placement I went to see a prisoner who had done something incredibly bad – he’d murdered two people. But he went to prison, thought about what he did, repented for what had happened and made the most of what was available. He’d been in prison for 20 years but every day he read a new book. He had read 7,200 books, and I don’t know any academic or professor who has done that. He was in a position where his freedom was most restricted, but still did something really positive with his time.

Conclusion

If I had the opportunity to talk to my 18 year old self before I had my first medical school interview this is what I would say to him: There is nothing wrong with the ‘boring and clichéd answers.’ Most doctors who I know practise medicine because they want to help people! A lot of the advise you’ve been given by people in your sixth form is well intended, but wrong!

If you’ve read this article and you are currently practising medicine, or you are thinking of applying to medicine, get in touch. I would love to hear how your motivations for practising medicine have changed over time.